department of nostalgia - (or the alhambra at night)

the department of nostalgia is the refuge for ornament, illusion and trickery. it harbours conflicting stories and multiple histories surrounding the elusive past lives and half lives of disused spaces, borrowed material and disappearing places and objects.

the department of nostalgia exists in cities, landscapes, suburbs, shops, streets, homes, offices - everywhere. it observes the ever expanding archive of museums, monuments, period films and tv shows, paintings, postcards, photographs, souvenirs and even vintage clothing – formerly known as second hand shops – where the past is re-inhabited by new occupants, or placed in a glass display.

the department of nostalgia glorifies the past as a romantic ideal, reconfigures events, characters and identities. this romanticisation of history is a welcome respite from modernism.

the light cast on the surfaces of the alhambra during daylight evokes a sense of gods presence on earth. this is an architecture of illusion and trickery – also employed in modernist and white minimalist architecture. but the alhambra at night is equally tantalising – an effect created by charm, nostalgia, myths and legends. the department of nostalgia values darkness as much as light, and the spatial and surface complexity required to cast shadows and uncertainties. it is an interior space festooned with rich tapestries and flickering candles, a garden of earthly delights.

dreams, nightmares, fake histories, architectural hoaxes, and ghosts parade in the shadows of the ornamental surfaces. the tourist audio guide activates the imagination with past events recounted. in these observed rituals of a newly refurbished past we glimpse fragments of an elusive utopia, fictional and intentionally romanticised.

‘if the traveller does not wish to disappoint the inhabitants (of a city), he must praise the postcard city and prefer it to the present one, though he must be careful to contain his regret at the changes within limits: admitting that the magnificence and prosperity of the metropolis when compared to the old, provincial city cannot compensate for a certain lost grace, which... can be appreciated only now in the old postcards, whereas before, when that provincial city was before one’s eyes, one saw absolutely nothing graceful and would see it even less today, if the city had remained unchanged; and in any case the metropolis had the added attraction that, through what it has become, one can look back with nostalgia at what it was.

beware of saying to them that sometimes different cities follow one another on the same site and under the same name, born and dying without knowing one another…at times even the names of the inhabitants remain the same, and their voices’ accent, and also the features of the faces; but the gods who live beneath names and above places have gone off without a word and outsiders have settled in their place. It is pointless to ask whether the new ones are better or worse than the old, since there is no connection between them, just as the old postcards do not depict the city as it was, but a different city which, by chance, had the same name as this one.’

Cities and memory 5, ‘Invisible Cities’, Italo Calvino.

Anam Hasan - Infiltrating the lloyd's building.

Department of Nostalgia: Dunkirk

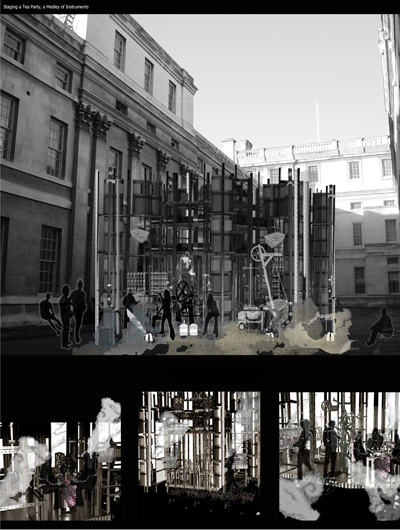

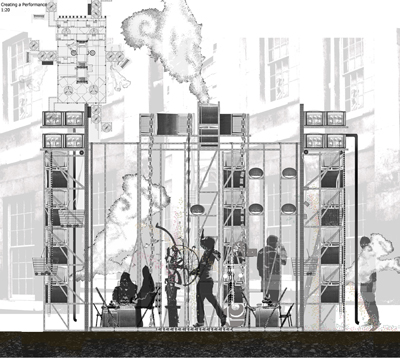

The Desert(ed) Hotel is composed of ‘programmatic sequences that suggest secret maps and impossible fictions, rambling collections of events all strung along a collection of spaces’ (Tschumi): diving into the fuselage of an airplane, a mechanised tea party, walking home along the dunes, sleeping on an airplane wing. ‘The events unfold frame after frame, room after room, episode after episode’ (Tschumi).

We asked students to design a hotel on the site of a series of concrete bunkers tilting in the sand dunes outside Dunkirk, built during World War 2. Flanked by a ruined 18th Century french military barracks, it’s a contested territory occupied by Belgian, French, German and British armies over time.

The paths of movement inscribed in the project are derived from military manoeuvres which took place on the site during world war 2. Where the visitor arrives at the hotel, he takes the same path as the German tanks took when they commandeered the fortress. The rooms are positioned where the parachutists landed, randomly blown across the dunes by winds. The pathways to the rooms retrace the movement of the antiaircraft guns. On the gun emplacements, guests dine and gaze at the horizon between sea and sky, mimicking the viewpoints of the gunners targeting this same vista. Barbeques replace the exploding shells.

‘If the reading of architecture was to include the events that took place in it, it would be necessary to devise modes of notating such activities….movement notation derived from choreography, were elaborated for architectural purposes….Architecture ceases to be a backdrop for action, becoming the action itself….Architecture becomes the discourse of events as much as the discourse of spaces’ (Tschumi)

Chapter 1: The Nightmare

Dunkirk saw the evacuation of 340,000 British troops in three weeks in 1941, the last pocket of unoccupied territory as the Nazis advanced. Try to imagine the previous occupants of these spaces, French officers amidst chestnut horses burning fires at night, British footsoldiers waiting for boats to bring them home, or Germans parachuting in from the sky or arriving in a panzer tank. Hours spent looking out to sea from a bunker, a vast expanse of landscape regulated by a crosshair target on the horizon, revealing the next chapter of your life.

The site evokes a multiplicity of occupants, signs written in a cacophony of languages and architectures, violent but beautiful, impersonal yet intimate: not unlike the program for a hotel – absence follows bustling presence follows absence again.

War is replaced by play, but not forgotten. The deserted hotel is a place to erase the past and create alternative futures, the replication of a game but with different rules. New sounds intrude upon the silence, a progressive shift from one reality to the other.

Chapter 2: The Dream

30 shiny metal aircraft are recycled to construct the deserted hotel, salvaged from Arizona. The hotel is a stage onto which the lure of the desert is projected, extending boundaries of event, communication, operation and visibility. Necessity gives way to luxury. The hotel speaks the language of machines, visible yet invisible.

The hotel is a baroque tapestry of fictions in search of an author.

As time passes, the occupants move on and are replaced by new occupants. Year upon year, the list of guests who stay at the hotel will get longer, one day the register will be lost, and with it the memory of the original occupants.